After a lengthy campaign by activists and protests against violence towards women, the government has announced that misogyny will now be considered a hate crime in England and Wales.

The concession was announced on March 18th in the House of Lords by Home Office minister, Susan Williams, following protests that have been highlighting a number of amendments to the domestic abuse bill that is currently being passed. Williams stated that the government “will ask police forces to identify and record any crimes of violence against the person, including stalking and harassment, as well as sexual offences where the victim perceives it to have been motivated by a hostility based on their sex.”

The Crown Prosecution Service defines the term ‘hate crime’ as ‘a range of criminal behaviour where the perpetrator is motivated by hostility or demonstrates hostility towards the victim’s disability, race, religion, sexual orientation or transgender identity’. All crimes that police suspect to be motivated by hostility towards gender are required to be recorded in England and Wales. This could apply to murder, sexual offences, domestic violence, harassment and stalking.

Gather is a local Cornish organisation that provides support to individuals affected by sexual trauma. Their founder and director, Lily, explains that misogyny is a hugely cultural issue, and that women have been playing a certain role for a very long time. “We are now beginning to witness women standing forward and stepping into more masculine roles that men have predominantly occupied”, she says. “This can appear quite threatening, especially to men that struggle with the idea that they have to upkeep the role of being masculine”.

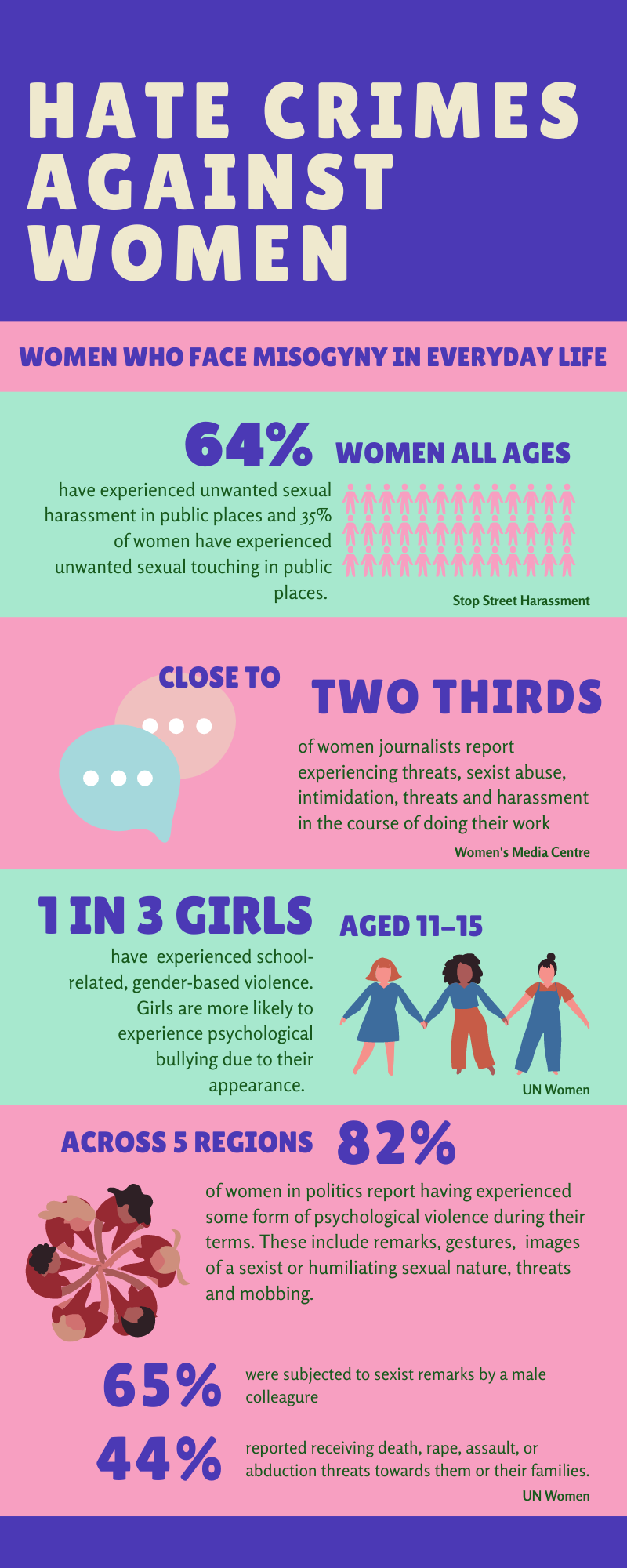

UN Women found that 82% of women in parliamentary positions, across five regions, had experienced psychological violence during their terms, ranging from remarks, threats, mobbing and death, rape, assault and abduction threats towards them. 65% percent had experienced in-person sexist remarks by male colleagues in the workplace. Similarly, the Women’s Media Centre found that nearly two thirds of women journalists experience sexist abuse, intimidation, threats and harassment whilst doing their work.

These actions have been shrugged off for so long, says Lily: “It’s very important that we’re encouraging women to report any type of harassment, especially these misogynistic acts that are based upon hostility and sex, and are specifically male towards female violence”. By putting down a zero-tolerance policy, women will feel more confident in reporting crimes.

However, Lily adds, “the justice system itself doesn’t really cater to these incidents – there isn’t a lot of faith in the justice system for survivors, and that works the other way too, the perpetrators are more likely to commit an offence because the likelihood of them getting prosecuted is so low”.

Recognising misogyny as a hate crime will allow tougher sentencing to be enforced where misogyny is a factor. However, the move is only on an experimental basis as the Law Commission believes it will not necessarily bring more offenders to justice.

The organisation, Citizens UK, began the misogyny hate crime campaign in Nottingham in 2015. They believed that by making misogyny a hate crime, it will give police a better idea of what hate crime looks like in the UK, allowing them to respond better and create intervention strategies. Statistics from their report show that gender-motivated hate is already a factor in 33.5% of existing hate crimes, yet over six in ten victims will not report the hate crime that they have experienced.

“I don’t feel a huge amount of faith in the system, myself as a survivor, because I’ve seen it fail people who have been through hugely traumatic incidences and there’s been evidence, and still there will be no prosecution and no justice”, says Lily. “It is something that is not really spoken about and perpetrators feel a sense of safety in that – they won’t get called out because there is a lot of shame about being a victim; we need to break down the secrecy and shame”.

“I do think it’s good for women to report these things, but whether the perpetrators will be prosecuted is another matter”, she continues. “We need more support and funding into women’s services and education for both men and women, and we need to raise the next generation in a world that doesn’t shy away from the subject”.

Lily concludes, “I’m not naïve in the sense that I think anything is going to stop happening. Unfortunately, these things are going to keep happening. I think all we can hope is that the women who come after us are better equipped for these situations and that they have a legal system that serves them rather than fails them”.