The breakup that ended my first, proper adult relationship was a catalyst for a long spell of restless (sometimes wine-filled) nights, trying to curb the impulse to send a desperate text to the one person at the forefront of my mind. I had always been fine with being alone. Now, something I once cherished had become a terrifying prospect. Breakups are alienating in the way that no two are the same; the uniqueness of the situation can render people’s well-meant affirmations and pep talks useless, but a wave of self care apps curated with newly-single people in mind might have potential to offer a small way of soothing the sting of loneliness.

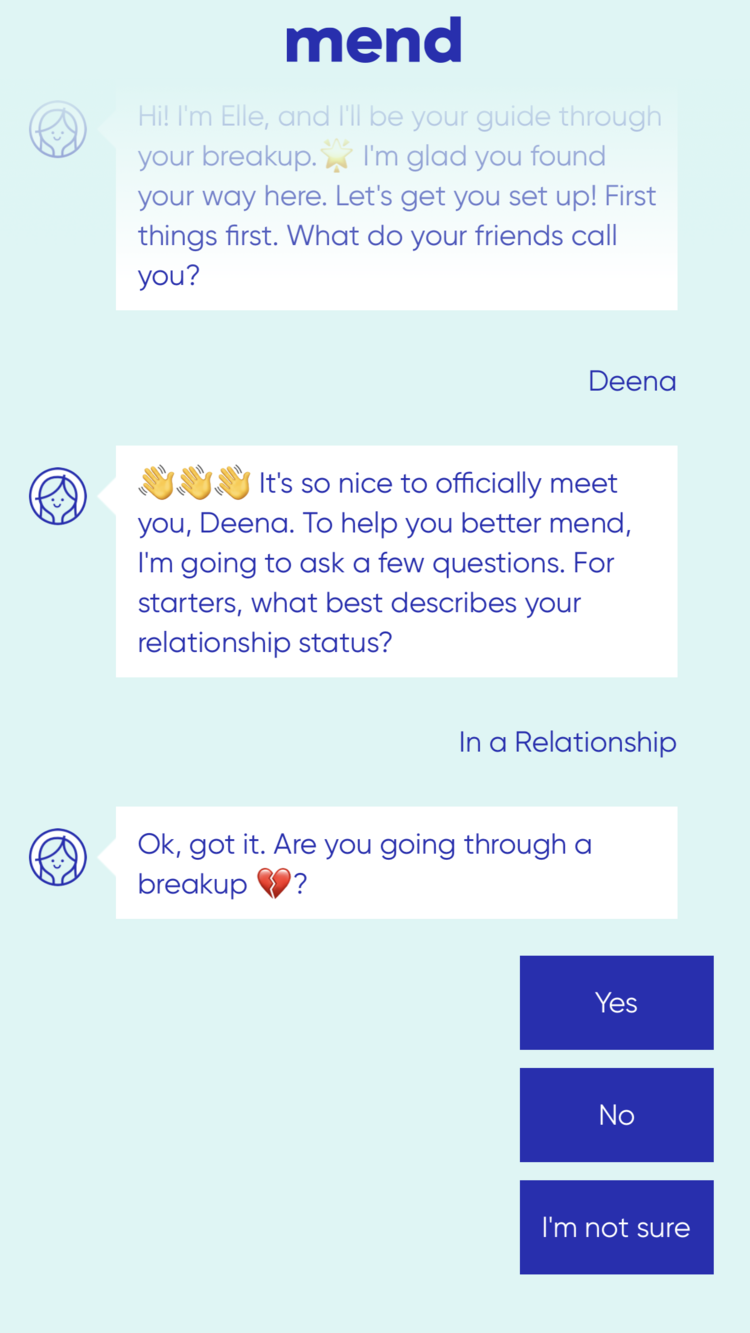

Founder and CEO of Mend, Elle Huerta, had recently moved to San Francisco and was living alone when she went through the breakup that inspired her app. “I was fairly new to a big city, and I had my work friends, but in a lot of ways, I felt isolated,” she said. “I started seeing a therapist which was incredibly helpful, but then I would struggle through the periods of time in between each session. Heartbreak is 24/7.”

Fascinated by the science and psychology of love and relationships, Huerta wanted Mend to be like a “best friend who also has great advice” and provide comfort during those first few days that are particularly sore. It encourages prioritising your relationship with yourself, be it through journaling, logging daily self care activities, or listening to audio trainings informed by credible advice from qualified mental health professionals.

Elle isn’t alone. In 2015, founder of Stila Cosmetics Jeanine Lobell and therapist Jane Reardon came up with Rx Breakup, a “30-day, 3-step program” that provides tools to help you compartmentalise your thoughts and feelings through analytical writing exercises and essentially helps you to replace unhealthy coping mechanisms with positive change, tailoring your experience of the app in a way that is completely personal to you—as opposed to what can sometimes be generic, empty advice. “I’ve read hundreds of self-help books and I find them so redundant and repetitive,” Reardon told Vogue. “I noticed that [when] treating people with depression, they need to be very conscious to start modifying their behaviour.”

In 2017, Australian author and relationship columnist Zoë Foster Blake founded Break-Up Boss; an app designed to virtually smack your hand away when you’re about to cave and contact your ex. Heartwarming illustrations serve to remind you of all the best bits about being single (always getting to pick what’s on TV, getting to move to a different country if you want to) but its most impressive feature lets you vent your feelings in a fake text to your ex—rather than having to deal with the looming realisation that you’ve actually sent an undignified 2AM paragraph the next morning.

“The ‘no send’ letters and journaling etc I have seen in these apps are all traditional psychotherapeutic methods of releasing pent up emotions,” acknowledges Counselling Directory member Beverley Hills. “However, there is no room for face-to-face feedback or discussion where several perspectives and history of patterns of behaviour are explored, therefore the personal journey a client takes with one of these apps could be very one dimensional. Of course, all of my clients have complete autonomy as to how they live their lives outside of the counselling room, however, I would advocate caution in that there might be some conflict, especially if the apps are not looking at past relationship dynamics.”

For Verity, who downloaded Mend a couple of days after her breakup, it has been a more accessible alternative. “I have used face-to-face counselling before and I wanted that a lot but couldn’t afford it, so this was the next best thing,” she says. “I was constantly calling my friends and family but I didn’t want to keep bothering them. This way you aren’t waking anyone up in the middle of the night and the app won’t be offended if you don’t take its advice.

“I rated my mood as being the worst possible every time I used it. By the time I got to the point where I would have started rating my mood higher, I got rid of the app because I’d pretty much forgotten about it—which was a good sign. This was about three months after my breakup.”

Heartbreak can be a nebulous thing, and an inherently isolating experience, but studies have found a mutual presence of dopamine in both romantic love and addiction; offering somewhat tangible validation as to the emotional trauma that comes with a breakup.

In an article on Huffington Post, psychologist at Stony Brook University in New York, Arthur Aron, commented on the relationship between the two, explaining that “intense passionate love uses the same system in the brain that gets activated when a person is addicted to drugs,” confirming that people who are obsessing over an ex —irrespective of the reason— may exhibit similar feelings to those of an addict craving a drug.

“I think there’s still a lot of stigma around heartbreak; [it’s seen as] something you should just be able to ‘get over,’” says Huerta. “It feels like withdrawal—it temporarily changes your neurochemistry and physiology. So many people are dismissive of breakups, but anyone who has been through a breakup or divorce knows just how debilitating one can be.”

The wake of these apps is appropriately timed, with self care becoming increasingly a part of millennial culture and technology allowing us to be almost instantly available to each other—they offer a convenient way to facilitate the moving on process in your own time and without being limited to the confines of a doctor’s room. “A digital pocket coach for your traumatised, fragile, gorgeous little heart” is how Zoë Foster Blake described her app to Who Magazine. “After all: Why should breakups be the boss of your life, mood, personality, diet, social life, sleep patterns, and (now ravenous and atrocious) drinking habits? Fuck that.”

Hills advises that users go into entering any kind of data into personal development apps with eyes wide open, and maintains that one-to-one interaction is still very important, given that there is ultimately no such thing as guaranteed privacy when talking about conducting anything online; “[It’s] why face-to-face therapy is a more effective method. We are sworn to confidentiality by our ethical framework to which we adhere our practice,” she explains. Meanwhile, for people like Verity whose internet history consists of searches that are already “pretty heartbreak heavy,” privacy isn’t a huge concern.