It was not long after Christmas. As many do, I struggled into work and felt that the weight of many mince pies had crept on. Time to count the calories again. Fitness gurus were followed on YouTube, new pairs of leggings and trainers were ordered, and I began browsing my Instagram for fitness ideas and inspiration.

You see, there’s this useful algorithm on ‘insta’ which allows you to quickly find other hashtags related to the one you’re currently searching, and click from one to the other. #fitness, #healthy, #weightloss, #caloriecounting, #inspo. That last one would turn out to be a mistake. Among the many colourful images of fruit salads and jogging bottoms was a vision of bony shoulders and emaciated ribs. I had stumbled across a community of, primarily teenage, girls dedicated to encouraging each other’s, and their own, self-starvation.

I found myself forever thinking of how easily I had stumbled across this material by accident

Of course, I had heard of the pro-anna online community before but it had always seemed to exist in the shadows of the internet, in its own little corner of obscure online chatrooms. Being confronted with it so graphically, and on one of the biggest social media apps in the world, was a great cause for concern and morbid curiosity. I began reporting posts more actively than usual, particularly those encouraging followers to engage in self-starvation, self-harm and even to commit suicide, but also posts using videos of violence and racist language. Sometimes I was successful, but many times not. I found myself forever thinking of how easily I had stumbled across this material by accident, and how easily I could be just 13 years old.

Shortly after this, I noticed that Instagram had found itself in the headlines in a bad way. The death of Molly Russell, a teenager who had committed suicide in November 2017 after a period of viewing materials such as these on the site, had been picked up by the media. Her father, Ian Russell, had come forward with his concerns at what he had discovered his daughter had been viewing online, particularly on Instagram and Pinterest, and his shock that these sites had not done more to protect vulnerable users like Molly.

One of the journalists who initially interviewed Russell, and worked with him to raise public awareness of the issues surrounding Molly’s’ death, was the BBC’s Tony Smith, whom I was able to speak to in an interview. At first I ask him, ‘obviously a lot of the media surrounding the case with Molly Russell do seem to pin quite a lot on Instagram and Pinterest, would you say that that’s fair?’

“We interviewed Molly’s dad in November, in a very emotional interview. The headline that came out of the piece, from our point of view, was very much that Instagram and Pinterest had a lot more work to do in this area. Ian Russell was very keen to highlight the kind of material Molly had been looking at and was quite angry about it. He couldn’t understand why it was allowed on a platform that was OK for 13-year olds.

He feels dreadful about it, and blames himself, as any father I think would

A lot of the comments on the piece went along the lines of ‘It’s not about Instagram, it’s the father’s responsibility, what was she doing on her phone’ ect… He absolutely feels huge amounts of personal responsibility. He’s not trying to pin the blame on Instagram in any way. He feels dreadful about it, and blames himself, as any father I think would, but he thinks Instagram certainly played a part in her death.”

Continuing down that path, I questioned him ‘did Molly give any other signs that she may have been suffering mental health issues?’

“About a year before she took her own life she was acting pretty down, not feeling very sociable with friends. She was going through a difficult spell. He accepts that she was suffering from some kind of depression that was not caused by Instagram in any way. She had gone to Instagram to look for help, and as it happened, she seemed in real life to be getting better. They had had a conversation to reassure her that she could talk to her family about how she was feeling and she just went ‘Oh, it’s alright Dad, I’m fine’ and so he was unaware of what she was doing on Instagram.”

That answer gave me reason to pause. Our stories are of course not similar, but I had started this article myself on a quest to seek help with something online, that had fallen down a dark rabbit-hole. I stopped to think of how I would have felt, responded or acted if I had been Molly’s age. Or prone to depression, anorexia, bulimia… It’s a shuddering notion. I asked Tony what he thought of the actions Instagram had taken in recent months.

“I think it’s interesting that Instagram has said they’d take down the self-harm images, but that wasn’t necessarily what she was even looking at. The ones that we know she was looking at were these very dark cartoons, and memes about suicide. Depressing slogans and poems. That’s not what Instagram has said they’ll deal with at all, so this whole community will still be there”

There is material on Instagram that shocked me, and I’ve been a journalist for 25 years

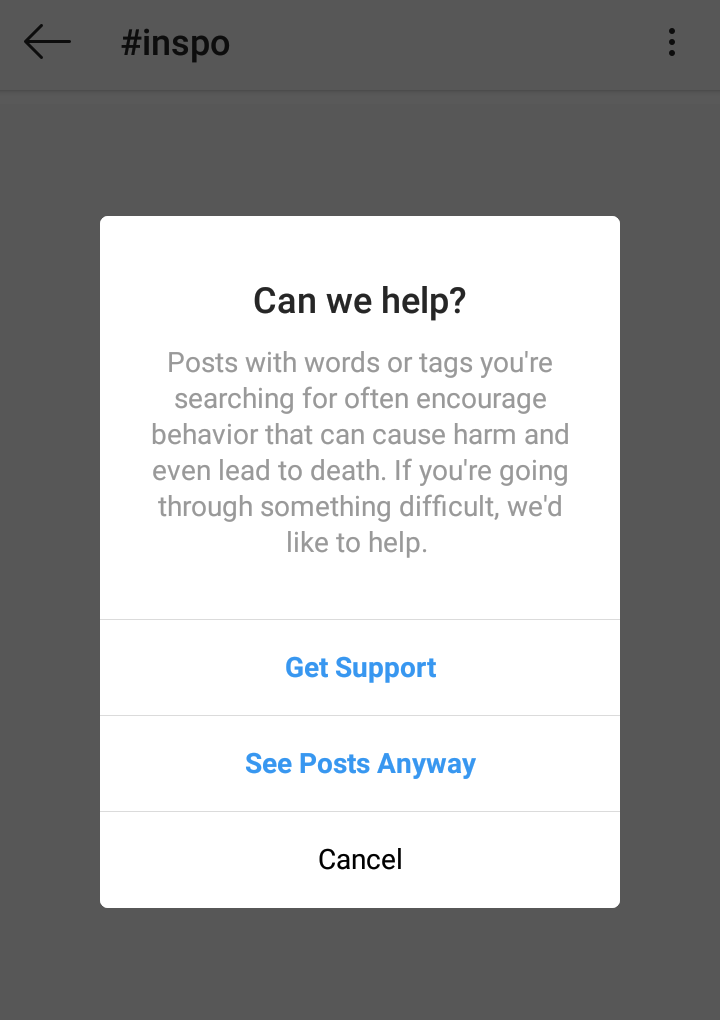

Do you have any thoughts on the ‘sensitivity screens’ and warning signs they’ve been using more recently?

“I think that’s a nonsense because you can just ignore it. There are very, very strict rules about what we can show on TV around self-harm and suicide. Before the watershed, we had to blur a lot of our images, and the worst of the stuff that we found we couldn’t show at all. As broadcasters, we’re bound by all these rules to protect the people that are watching, but social media sites like Instagram don’t have to follow these rules. They claim not to have any responsibility for the material on the site, that they are not a publisher. And I certainly think Ian Russel would say that’s wrong. There is material on Instagram that shocked me, and I’ve been a journalist for 25 years, I’ve seen some pretty horrific things around the world. I think what they’ve done in the short term is ineffective, in my view and Ian Russel’s view there’s no place for that content on a platform for 13-year-olds”

Do you think this situation is similar to that of the pro-anna community?

“We’re doing a follow-up piece about anorexia sites. A lot of them put ‘trigger warning’ which is pretty naive, teenage girls thinking it’s ok to put something out there so long as they write the words ‘trigger warning’, that it’s not going to get them into trouble, it’s not going to hurt anybody”

In short, though sites like Instagram or Pinterest have made a few steps towards protecting vulnerable users, the steps they have taken appear to have been poorly informed in terms of mental illness, and poorly researched in terms of looking into the reality of what Molly Russell was viewing and posting. Through providing the option to view content that is triggering to mental illness, it is the belief of many connected to Molly that, even now, the site hasn’t done nearly enough.